By James Yékú

According to one urban legend, any party without Jollof Rice is just a meeting, but on social media, it matters significantly whether that Jollof is of Nigerian or Ghanaian origins.

It certainly does for some AFCON supporters at this year’s tournament whose vociferous performance of AFCON fandom has been a little more intense than in previous editions of the biennial tourney, not with the gastropolitical dimensions of the perennial social media jousts and banters over Jollof Rice and with the ongoing competition in Ivory Coast in mind, other tantalizing delicacies.

For the initiated, and those familiar with online social relations between Nigeria and Ghana, the Jollof Rice rivalry, the popular tomato-sauced, orangey rice dish originally of the Senegambian Wolof, may have become tiring, but after Nigeria’s win over Angola in the first of four intriguing Quarterfinal matches in Ivory Coast last week, attention on social media turned to another delicacy, the antelope meat.

If you are wondering, all this makes sense with the AFCON participation of Angola, a country on the coast of Southern Africa. Angola’s national team, fondly referred to as the Palancas Negras—meaning the giant sable antelope, surprised many as they came out tops in a group comprising two of the ten best-ranked teams in Africa, Algeria, and Burkina Faso; but the sable antelopes quickly became a staple of online banters among Nigerian fans when they faced the Super Eagles.

When an Angolan X account posted “Bring Them On” in response to the confirmed fixture between the Palancas Negras and the Super Eagles at the end of the second round of matches, what followed was a sea of comments by many of Angola supporters mocking Nigeria’s bluntness in front of goal, something the Angolan team up to that point had done well in Ivory Coast. The official X handle of DStv in Angola went as far as using AI-generated images to tease Nigeria’s Victor Osimhen. The Napoli striker had scored only a single goal in 4 games while Angola’s Gelson Dala had 4 goals already.

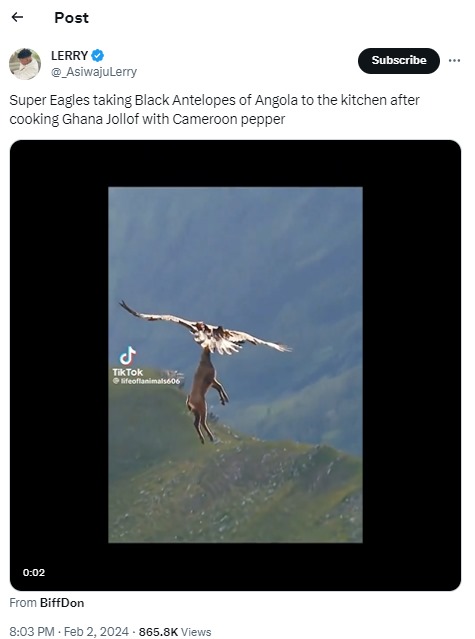

With a Nigerian victory guaranteed after Ademola Lookman’s delicious first-half goal, the Nigerian handle of DStv saw an opportune moment for revenge, as the large Nigerian contingent online immediately responded with a torrent of tweets as a tongue-in-cheek clap-back against their opponents. As one Nigerian X user suggested, it was time to have Ghana Jollof with Antelope meat sprinkled with Cameroon pepper. Other variations of this sentiment flooded the internet.

Anyone who has followed the matches in Ivory Coast can appreciate the reference to Cameroun and Angola in the context of Nigeria’s victories at AFCON. The allusion to Ghana is a bit odd except, of course, if before the match with Angola, you were a Ghanaian fan who had imagined an encounter that excites with schadenfreude. Taking aim at a squashed Ghanaian pleasure in Nigerian misfortune, the banters over Jollof Rice were predictably back at the table.

For the Nigerian, therefore, to have “Ghana Jollof” that is made with Cameroonian pepper and Angola venison offered an ironic reluctance to accept the inferiority of Nigerian Jollof to mock their West African brothers and Ghana’s early ouster from the 2024 AFCON.

And the jokes and teasing are not just a fan affair, as some players join in the conversation and take the game to a different level through their amusing performance of elite pettiness. Beyer Leverkusen’s Victor Boniface, who departed the Nigerian camp after picking up one of a string of injuries that hit the Nigerian camp just before the start of the games is at the heart of some of these jokes. Responding to a Ghanaian YouTube personality and content creator Kwadwo Sheldon who said in a video that Ghanaians “can’t allow Nigerians to win #AFCON” because Nigeria already dominates Afrobeats and keeps dragging Jollof Rice with Ghana, Boniface fired back, mocking the Ghanaian team: “your mate dey semifinal, you dey drag joffof [Jollof] rice.”

All this matters not because the social media banters are a front for a more insidious backstory of subtle bigotry. Food and sports might be cultural systems, but the mixture of the two in the field of playful mockeries entices other symbolic meanings. The anthropologist Arjun Appadurai has since called food a system of “gastro-politics,” referring to the conflict over specific cultural or economic resources as it emerges in social transactions around food. If the Cameroonian expression, “politics of the belly” is relevant to scholars like Jean-François Bayart who try to understand patron-client relations in postcolonial African states, this year’s AFCON makes it more relevant both on and off the pitch, with social media the perfect battleground for its recruitment into the conviviality of soccer fandom online.

Hence, content creators using TikTok and X to share humorous posts about cultural dishes as a means of participating in soccer banters are, in fact, unbeknownst to them, engaged in broader political conversations. For example, while acknowledging the Nigerian noise over the Super Eagles wins, some fans from Ghana keep reminding Nigerians that cities such as Accra and Legon have constant electricity to watch the AFCON matches, something that cannot be said of Lagos and Abuja. Recruiting the politics of infrastructure—both in terms of its presence and lack—is telling and reminds us that these online battles embed other meanings.

Or how does one explain the tweet by a Nigerian fan who wrote: “Angolans, pack your bags. There’s only room for one corrupt oil-producing country in this tournament and that’s us”? If you’re a psychologist or linguist, you might appreciate the cultural value and pragmatics of bantering as a friendly, enjoyable mode of conversation where people make jokes and funny remarks about each other, but if you are a Nigerian or Ghanaian fan on social media, the stakes are higher.

Of course, some may suggest these banters and friendly insults, aside from encouraging unhealthy enmity, are as unwholesome as the other distracting mechanisms that divert from the actual material conditions of existence in these countries. The proponents of such a view on sports more generally, which is rooted in the Classical leisure and entertainment spectacles of the Greco-Roman ruling class, may even hold that sporting pleasures and social media are ideological affordances of the powerful, which blind people to their actual conditions, the impoverished circumstances of everyday people.

Of course, sport is a complex terrain of the political, and that’s precisely the point, but these criticisms also miss the larger picture sometimes, given that sports also unify and often become recruited to fight systemic power. It goes without saying that social media banters serve to uncover the bonds and commonalities between countries like Nigeria and Ghana. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that they might spill over into violence.

Because there’s always that tension bubbling under the surface of online banters, the participants in these conversations definitely know that repartees and chitchats transcend the space of the online world, entering into concrete spaces in which they structure events.

One Sir Dickson even asked Nigerian online fans to respect themselves, writing that if “we get to play South Africa [as indeed the AFCON Semis will play out], please respect yourself and drag Ghana. We are not bantering South Africa. It is the Haters Cup and South Africans take the hate to the street.” To be clear, the online rivalry between Nigeria and South Africa, recently exacerbated over Western misattribution of the latter’s Amapiano music to Nigeria, manifests in other contexts, but football generally tends to amplify things.

James Yékú teaches courses on social media, and African popular cultures at the University of Kansas, Lawrence.